Seafood Fraud

The misrepresentation of seafood species is so rampant in the United States that it’s become a textbook science project for high school students, who purchase seafood and then test samples of fish DNA to determine the correct species. Mislabeling seafood, or representing seafood, as belonging to a popular species is fraud, and seafood fraud is flourishing.

The most common fish fraud occurs with fish labeled as Alaskan salmon, red snapper, or Atlantic cod; when tested these are often other species that are cheaper or more readily available. Since many fish are sold as fillets, it is almost impossible to tell the species, as the head and fin markings are gone. The ability to know the source of a fillet is nearly impossible until rapid DNA tests are widely available.

One evening, four of us Alaska Natives were finished with a long meeting in San Francisco and decided to have dinner at a well-known local establishment. When the waiter was reciting the specials, he noted that they had just obtained fresh salmon. You could see eight ears perk up, and one skeptically asked, “Is it wild salmon, or farm raised?” Alaskans are notoriously picky about our salmon.

“It was troll caught,” the waiter said, “and we just got it in today.”

One member of our group said that it seemed out of season, and he would bet that it was farm raised. The waiter insisted he knew it was troll caught. We made a bet: serve us a fillet as an appetizer. If it were farm raised he would buy the fillet; if it were troll caught we would pay for it and tip him thirty per cent of the bill.

The salmon arrived. The four of us looked it over before looking at each other with arched eyebrows. Simultaneously taking forkfuls of the meat, we chewed, and then in unison said, “Farm raised.” The waiter said he would check with the chef.

The four of us had eaten salmon since infancy; we had caught and filleted thousands of fish. Our taste buds were familiar with wild Alaskan salmon: the firmer texture of king salmon, the oily nature of the fish, as well as the slightly stronger flavor. The waiter asked the chef, who told him it was fresh, farm-raised salmon from British Columbia.

.

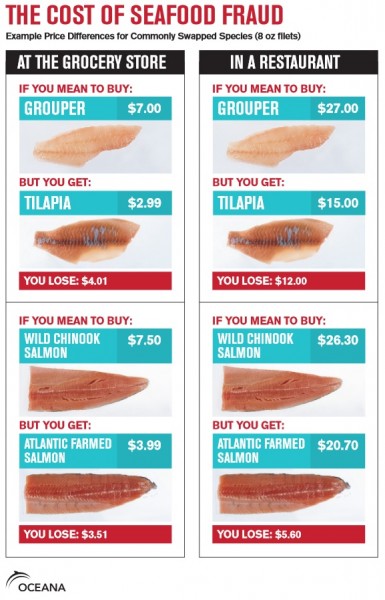

For two years Oceana.org surveyed fish from 674 retail outlets in twenty-one states to determine if the seafood was correctly labeled. They found that one-third of the fish was incorrectly labeled.

The highly prized red snapper was mislabeled 113 times out of 120. In the sushi restaurants of New York City, every single restaurant tested had mislabeled fish. The highest mislabel rate was in southern California, where 52% of the fish was mislabeled. In Seattle, a town that prides itself for its seafood, every snapper sample was mislabeled.

Sushi venues nationwide have mislabeled fish with health consequences. Responsible wholesale and retail chains purchase from good sources; however, the temptation to get a bargain can have deadly consequences. Of the white tuna sampled, 84% were escolar.

Escolar is a delicious fish, but it contains a lot of wax esters that are indigestible to humans. Typically, the fish leaves the person as an “orange droplet diarrhea” called keriorrhoea. This means that the esters make their way to the colon because the small bowel has no way to digest these into a fatty acid that can be absorbed. However, depending upon the types of bacteria, some individuals are able to eat this fish with impunity. There is no method of cooking the fish, cleaning, or storing the fish that makes changes this. If you have this symptom after leaving a sushi bar where you consumed white tuna, tell the sushi bar immediately.

Seafood fraud can occur at any step in the supply chain, and besides overpaying for a piece of fish there are four significant issues:

1) It can be a source of illegal fishing. Fish that are harvested illegally, through long-lines with bycatch or by harvesting endangered species, will often be sold as some other species.

2) Knowing the source of the fish ensures that the fish are obtained from a sustainable source. When fish are mislabeled, it is impossible to know the source.

3) Health hazards: fish that are caught from sources that have increased mercury or PCBs represent severe risk to fetal development, as well as risk to adults. Since there is no smell or taste to these contaminants, and they are not cooked out of the fish, this can go undetected. King mackerel, a fish on the FDA’s list to avoid due to high mercury levels, was sold as grouper in a grocery store in South Florida.

4) It misrepresents the availability of seafood. If you think you are getting a steady supply of red snapper, and yet it is endangered, you have a false assumption of the true nature of the creatures.

The ability to get fish whole, provides positive identification of the species

Reliable partners:

Knowing the fishmonger is a key in the supply chain. While Seattle, for example, had 18% of the fish mislabeled, those who go to Pike Street Market will be able to purchase whole fish that you can identify. Most fraud occurs when fish are bought as fillets, when even an experienced eye will have difficulty discerning one type of fish from another.

Some suppliers will track fish catch, such as Gulf Wild, where the fish includes a tracking number that is visible on the gill of the fish. You can go on the internet and track who caught the fish, where it was harvested, and where the fish landed.